For decades scientists and environmentalists have been warning about the threat to humanity represented by anthropogenic climate change, caused above all by the ever-increasing use of fossil fuels, which is causing the greenhouse effect to grow. And it is years, at least since the Kyoto Protocol of 1997, that the international community has begun to tackle the problem by agreeing to the binding objectives of reducing carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gas emissions – the main ones responsible, with deforestation, of climate change – released into the atmosphere due to combustion processes (in thermoelectric power plants, motor vehicles) of coal, oil and gas.

Today climate change is no longer just a threat: it is an established reality made of a progressive increase in the average temperature of the earth, multiplication and intensification of extreme weather events (droughts, floods), melting ice and rising sea and oceans levels, of accelerated biodiversity loss. A reality that is causing serious environmental, economic and social damage: just think of the progressive desertification of areas that until recently could be cultivated, which, especially in Africa, deprived of food large rural communities, and fuels the phenomenon of “climate migrants” (tens of millions already today); or the increasingly intense heat waves that hit many metropolis, with a significant number of deaths each year and a greater impact in cities inhabited by a large percentage of elderly population. If there will not be a strong acceleration in the rate of reduction of climate-altering emissions, as required by the Paris Agreement signed in 2016, and the average terrestrial temperature will rise by more than two degrees compared to pre-industrial levels (it already increased by almost one degree centigrade), the consequences of climate change will become catastrophic: not for the planet, which in its history has experienced even deeper climatic oscillations, but for us humans.

Why a European carbon tax?

The carbon tax is a response to all this, one of the most effective and timely. It is called “tax” but in fact it is not a tax: it is a mechanism that establishes a price for carbon emitted as a result of human activities. A mechanism whereby those who emit carbon would pay at least part of the cost borne by the community for these emissions.

Carbon tax has been discussed for some time: countries like Sweden have already successfully tested it, and recently French President Macron has launched the idea of a European carbon tax on all energy uses not included in the ETS (“Emission Trading scheme”), namely on emissions from the domestic sector, transport, agriculture, small and medium-sized enterprises. For Macron, the introduction of the carbon tax should be accompanied by the imposition of a tax at the EU borders equivalent to that paid by the European emitters, to avoid distortions of fiscal nature and consequently risks of loss of competitiveness for European companies or delocalization of production.

The direct benefits of introducing a European carbon tax would be multiple. The first is that it would give the European Union a tax revenue, marking an important step towards a Europe that is no longer just intergovernmental. In the hypothesis of a levy of 50 Euro per tonne, suggested by the High-Level Commission on Carbon Prices chaired by Stiglitz and Stern, in the coffers of the Union would come about 110 billion Euro, equal to about two thirds of the current Community budget (which is about 190 billion). To these would be added about 25 billion from the tax at the EU borders, and more resources related to the ETS system. In addition, a European carbon tax would allow, on the one hand, funding a program of investment and development geared towards energy innovation – higher efficiency, renewable sources – and in general support for the green and circular economy; and on the other, adaptation policies to climate change, i.e. the measures necessary to limit the social and economic impact of climate change.

But the carbon tax would also be a symbolically important choice to give Europe a new sense and a renewed future.

A community in an identity crisis

Today Europe is a continent, a community of peoples and persons, in an identity crisis: it has a very long past of global “hegemony”, but it struggles now in a tiring and perplexed present, and has an uncertain future ahead. We are coming out from a decade that has certainly been the most difficult and problematic since the construction of the European Union started: since the almost visionary will of a small group of great statesmen – De Gasperi, Schuman, Adenauer – has the European dream described by Spinelli, Rossi, Colorni in the Ventotene Manifesto begun to become reality.

Europe has experienced years of unfavorable economic conditions, of job losses, of increasing poverty, of so-called “austerity” policies that, in order to safeguard the balance of public finances, ended up undermining the welfare systems – that together with peace represent the most precious legacy of the last seventy years of Europe – and in some cases, as the example of Greece showed to everyone, have produced social catastrophes. This long cycle, economically and socially unfavorable, has made European citizens feel a widespread sense of disorientation, of distrust, almost of collective depression, and fueled reactions of refusal towards that model of “open society”, which is one of the most precious “trademarks” of Europe in the last seventy years.

Certainly these difficulties were due to global phenomena such as the disproportionate weight of finance, by its nature more “irresponsible”, socially and territorially, than the real economy. Other threats such as the one represented by Islamist terrorism have contributed too, as well as the strong intensification of migrant flows from the southern shores of the Mediterranean (whose perception is decidedly “overemphasized” by the majority of European citizens, but is a further sign of frightened and discouraged communities). And certainly they arise also from the incompleteness of the European construction, in particular from the marked deficit of democratic legitimacy of the community institutions, and then from errors and inadequacies of the European ruling classes: not so much the notorious “Brussels bureaucrats”, often referred to as the main perpetrators of the evils that are shaking Europe, but in actual fact – in the current framework of exquisitely intergovernmental rules that guide the functioning of the Union – the national governments and the political majorities of which they are the expression. But the crisis in Europe does not depend only on the internal dynamics within the borders of the “old continent”: it is an immensely deeper crisis, a profound and even paradoxical crisis, an outcome of the last thirty years of accelerated globalization. Yes, paradoxical: because on the level of social emancipation (notwithstanding the various popular beliefs on the triumphant neo-liberalism and on the “dictatorship of the markets”) the current, “infamous” globalization can already be considered as the most disruptive liberation movement from misery in human history. In the last three decades, despite the strong increase (over 50%) of the world population, the number of “absolute” poor, i.e. people forced to live on less than $ 1.25 a day, has decreased by 700 million. In China, the poor have gone from over 800 million to less than 150, in India they have decreased by 34 million. In Africa itself, by far the poorest continent, the rate of extreme poverty is constantly decreasing: it was 58% in 1999, today it is a lot less than 50%. Poverty reduction, which also saw the number of “almost-poors”, i.e. those living on less than $ 2 a day, decrease, was almost everywhere accompanied by a clear improvement in health and socio-cultural indicators: for example, in Brazil, one of the countries symbolizing the globalization process, in the last ten years, thanks to both a formidable economic growth and very intense policies to contrast poverty, child mortality due to malnutrition has fallen by 58%, illiteracy has decreased from 12.3 to 8.4%, the minimum wage increased by 72% and even the gap between rich and poor was reduced.

Where is the problem then, and where is the paradox? They are here, at home. This new season of history, that in global terms has led to a significant redistribution of wealth between rich and poor countries, and therefore bears an objectively “progressive” sign, in the West, and in particular in Europe, produces “side effects” of opposite sign: poverty increases, welfare systems become economically unsustainable.

Europe is getting smaller

In the current debate on Europe, its problems, its divisions and fragmentations, too often the historical dimension is forgotten, and in particular its past history in a medium and a long period of time: the one baptized by Braudel as the “visceral”, structural changes. A more difficult story to discover in the single events and in the short time of politics, often absent from the awareness of the contemporaries: but history influences at the roots events, politics and the life of contemporaries.

In this case, the medium period – not long, because this process is relatively rapid – saw Europe dealing with geography more than with history: due to its “creations” – capitalism, globalization –, Europe has become ever smaller and closer to its true territorial and demographic dimensions, as far as its economic and geopolitical weight are concerned: an epochal change, after more than a millennium of almost absolute hegemony over the world, and more and more crucial in terms of its centrality in regard to migratory flows, that are registering a continuous and increasing pressure from the south towards the north of the Mediterranean.

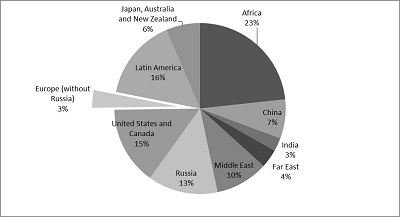

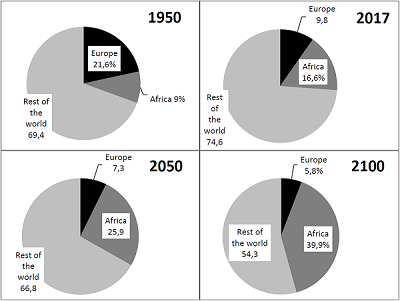

Europe accounts for 3% of the landmass of our planet, against 16% of Latin America and 23% of Africa (see Figure 1). As late as 1950, a little more than half a century ago, a fifth of the world’s population and twice the population of Africa were living on our territory; today we Europeans are less than 10% of the world population, and we will be just over 5% at the end of this century (see Figure 2). We are also much older than the rest of the world: one in four Europeans is more than 60 year old, about twice the percentage of over-sixty people in the world, and about 27% are up to 24 years, against 42% of “under 24” on a world scale. As for the economy, the European GDP in 1980 was a third of the world GDP, while today it is about a fifth. In the future, Europe’s weight loss treatment will only increase, both in demographics and in the economy. For example, the Africans, who a few decades ago were half of us Europeans, today are more than double, in 2050 will be more than triple, and in 2100 will be as many as the Asians; so it is expected that, precisely because of climate change, in the coming years hundreds of millions (!) of “environmental migrants” from Africa will be on the move.

These are trends that one can try to govern, but which cannot be stopped. Transmitting awareness of this is one of the main duties of truth and responsibility of the current European ruling classes, and is the indispensable condition for identifying ad-hoc solutions – probably there are none, only partial remedies for our “anxiety of the future”. As Europeans we are immersed in a very difficult passage not only for the communitarian construction begun seventy years ago, but for the history of European civilization: a changeover, in this sense, even more uncertain than the tragic one experienced in the twentieth century, which saw the convulsions of Europe still within an undisputed framework of global domination. Europe for over 1000 years has been the “dominus” of the world; certainly during this long period there were important changes: the progressive shift from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic coast of its economic center of gravity, the emergence and success of new and powerful “co-owners”, first North America and then Japan. But only in this initial glimpse of the third millennium did Europe see its centrality fall apart.

So, a first fact to be affirmed with force – a fact that in the current phase of European politics, dominated by sovereignisms and more or less explicit “euro-skepticism”, is not very fortunate – is that Europe is perhaps the only antidote to the risk of an unstoppable decline in the prosperity of us Europeans. If the pace of economic growth in the various parts of the world will continue in the coming decades at the current rates, in thirty years no European country will have the right to sit at the G7 table: no one, not even Germany. “More Europe” is the only insurance policy left, as Europeans, on the global scene.

After that, because this evidence shall persuade people in the flesh, a Europe radically different from the current one will be needed: a more democratic Europe in its institutions, much more mindful of the social dimension, of the wellbeing of its citizens, and a Europe that chooses to bet on its best vocations to create true, lasting and sustainable wealth.

Europe, to maintain an important role in the world, must follow two paths that are both obligatory: it shall become more and more a unitary geopolitical subject, and then focus on its talents, among which there is certainly the ability shown in the years to proceed faster than others on the way of an “ecological conversion” of the economy.

A “green new deal” to keep a leading role

Throughout the world, more and more economic actors, even large multinationals from energy to new chemistry, are taking up this challenge, the challenge of the “green economy” and the “circular economy”, and are demonstrating with facts that investing in “eco- innovation “ is not only “right “ but worthwhile. For Europe, this is not only an indispensable prospect helping to prevent catastrophic consequences for mankind from climate change and other global phenomena of environmental degradation (loss of biodiversity, air and water pollution, risks of depletion of natural resources). It is still an act of “virtuous selfishness”, the undeniable condition to remain, at par with the Asian giants and with the United States, a “big player” on the world economic and geopolitical scene. Europe needs, as many have been saying for years, a “green new deal”, and a European carbon tax can be one of the most solid bases for building it. Europe has all the assets – technological knowledge, cultural sensitivity – to cut first the winning post of a “carbon-free” economy. It has all the assets and it would have extraordinary advantages: because we import most of the fossil energy we use, while our renewable energy potential is largely superior to our needs today and tomorrow; and because the green economy to be developed requires much more quality – technology, labor – than quantity – raw materials –, and is therefore a terrain of economic competition particularly favorable to us Europeans. In the European Union, the ratio of renewable sources over total energy consumption is already today close to 20% : it is about 30% in electricity, almost 20% in heating, around 7% in transport. Until a few years ago, Europe was the undisputed leader in the renewable sources race; today there are big countries like China and India that are investing much more than us in energy innovation. A European carbon tax would give a boost to “renewable” Europe, but not only: it would indicate to all Europeans – businesses, consumers, civil society – the only realistic alternative to Europe’s destiny to become the periphery of the world.

Figure 1: How Much the European Territory Matters (% of total dry lands, excluding Antarctica)

Figure 2: How Much European Population Matters and Will Matter (% of world population in the years to 2100)

Source: World Population Prospects by UN, 2017

Log in